Napoleon Hill is the most famous conman you’ve probably never heard of. Born into poverty in rural Virginia at the end of the 19th century, Hill went on to write one of the most successful self-help books of the 20th century: Think and Grow Rich. In fact, he helped invent the genre. But it’s the untold story of Hill’s fraudulent business practices, tawdry sex life, and membership in a New York cult that makes him so fascinating.

That cult would become infamous in the late 1930s for trying to raise an “immortal baby.” But even those who know the story of Immortal Baby Jean may not know that the cult was inspired by Hill’s teachings, practically using his most famous work as their holy text. Don’t worry, the whole story of Napoleon Hill only gets weirder from there.

Modern readers are probably familiar with the 2006 sensation The Secret, but the concepts in that book were essentially plagiarised from Napoleon Hill’s 1937 classicThink and Grow Rich, which has reportedly sold over 15 million copies to date. The big idea in both: The material universe is governed quite directly by our thoughts. If you simply visualise what you want out of life, those things and more will be delivered to you. Especially if those things involve money.

The past few decades have been a profitable era for all sorts of self-help and business success books. Napoleon Hill blazed a trail for an entire industry. But Napoleon’s early work is seen as “the source” when people get deep into self-help and business success literature. Hill’s Think and Grow Rich is passed around in certain business and real estate circles like some kind of ancient text. In fact, when The Secret emerged on the scene in the mid-2000s, countless entrepreneurial writers would pen their own books, pointing to the works of Napoleon Hill as the true basis for what The Secret called the Law of Attraction.

You can see the influence of Hill in everything from the success sermons of Tony Robbins to the crooked business dealings of Trump University. In fact, you can draw a direct line to Donald Trump’s way of thinking through Norman Vincent Peale, an ardent follower of Napoleon Hill. Reverend Peale, author of the 1952 book The Power of Positive Thinking,was Donald Trump’s pastor as a child.

“You always, when the service was over, you said, ‘I’d have sat there for another hour,’” said Trump of Peale. “There aren’t too many people like that. It wasn’t the speaking ability, it was the thought process.”

The legend of Napoleon Hill has grown and morphed over the years. He really did live an extraordinary life, just not the life that his thousands of disciples over the years have claimed. It’s just too bad that Hill spent most of his life as an utter fraud—a fraud who by hook and by crook was constantly reinventing himself.

Napoleon Hill’s Wikipedia page sometimes warns that it’s written like an advertisement. Which pretty much hits the nail on the head. Hill’s entire life was an advertisement; one that spoke of honour and taught that if people visualised their dreams and narrowed down their own purpose in life, good things would come to them. And if the lessons in Hill’s writings “work” for some people, I say good for them. I’m not here to say that there’s nothing to be learned from some of Hill’s writings—especially those that speak of self-confidence, being kind to others, and going the extra mile for something you believe in. But the real story behind Napoleon Hill’s life is long past due.

After countless hours of research, I still feel like I’ve captured just a mere glimpse of the complex man that was Napoleon Hill. But it’s a glimpse that I share in the interest of uncovering Hill’s real life; a life that has been hidden to so many lost souls looking for answers in a confusing world seemingly without order or meaning.

Hill was a product of the late 19th century New Thought movement and the magic that came along with believing that mere thoughts could move mountains, or at the very least cure cancer. And after Napoleon Hill’s death in 1970, practitioners of the Prosperity Gospel would offer little but empty promises for their own enrichment. Somewhere in between we have the life of Napoleon Hill.

Cracks in History

If you pull up the website of the Napoleon Hill Foundation or flip through the official biography of Hill, released in 1995, it’s hard not to be impressed by the man’s supposed accomplishments. He was said to be an adviser to two presidents: Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Hill even claimed that he came up with FDR’s most famous phrase: “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Hill was a charlatan through and through. In fact, there’s no evidence whatsoever that Hill met President Wilson or President Roosevelt, let alone acted as a trusted adviser to both. There’s little evidence Hill ever met any famous person he claimed was an inspiration for his work, outside of Thomas Edison. But we’ll get to that later.

Hill’s most infamous claim was that he met and interviewed at length the industrialist Andrew Carnegie in 1908—the richest man in the world at the time. Hill said that Carnegie tasked him with interviewing the most successful men in business and learning the secrets to their success. But Hill only started making this claim long after Carnegie had died in 1919. Hill spent the 1920s telling of his great mission from Carnegie, and went on to write an entire book detailing his conversations with Carnegie. It was first published as Think Your Way to Wealth in 1948, then in 1953 as How to Raise Your Own Salary, and today published by the Napoleon Hill Foundation under the nameNapoleon Hill’s The Wisdom of Andrew Carnegie as told to Napoleon Hill.

Frankly, the entire book is laughable. What’s ostensibly a conversation between Hill and Carnegie is written in the garbled style of self-help, get-rich-quick nonsense that Hill would help popularise. And tellingly, in the official biography released in 1995, Hill biographers can’t help but concede that the book released about this meeting was largely fiction—or as they put it, “a somewhat contrived conversational format featuring Hill and Andrew Carnegie.” They insist that the meeting really did happen, just that Hill expanded it into a work that contained his own ideas about success. But the 300-page ramblings are so absurd as to be transparently a work concocted from whole cloth by Hill.

I contacted Andrew Carnegie biographer David Nasaw about the alleged meeting between Carnegie and Hill, and he told me he “found no evidence of any sort that Carnegie and Hill ever met.” I pressed Nasaw about whether there was any chance at all that Hill’s book could be based on real events. Nasaw replied, “Let me put it this way. I found no evidence that the book was authentic.”

Hill was involved in countless scams over the years. One of his earliest involved buying lumber on credit, never paying his suppliers, and selling the lumber to others for cash at rates well below market value. This, as you can guess, didn’t last very long before Hill went on the run. But that was just one of many scams that Hill would try over the years. Napoleon Hill was a man whose entire racket was reinvention—selling himself and his ideas as transformative. From his involvement with an infamous cult that used Think and Grow Rich as their most holy book, to embezzlement from his own charity, the most fascinating aspects of Hill’s many misdeeds have been forgotten by history.

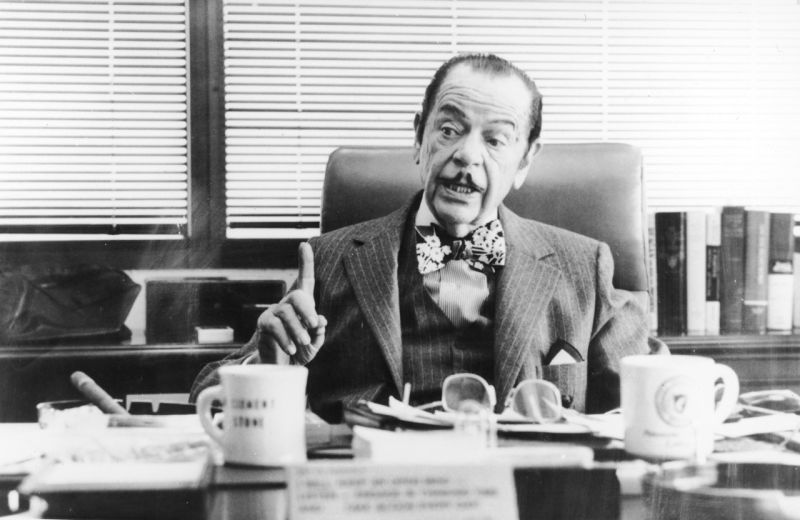

Donald M. Green, CEO of the Napoleon Hill Foundation (YouTube)

The Enduring Influence of Napoleon Hill

The man at the other end of the phone is rattling off a list of names and titles before he stops himself to learn why I’d called.

“The CEO of Chik-Fil-A… Arnold Schwarzenegger…,” he says with a low southern voice before pausing. “Who did you say you’re with?”

It’s November of 2014 and I explain again that I’m a writer and that I’m interested in the life of Napoleon Hill. I say that I might be interested in writing a story about him and that I’d like to see any unpublished works by the late Mr. Hill—most of all, his unpublished autobiography. I ask if I might be able to see it in person, provided I could make my way to Virginia.

“No, you can’t,” he says flatly before resuming with his list of people influenced by the late, great Napoleon Hill.

I’m speaking with Donald M. Green, the CEO of the Napoleon Hill Foundation. Mr. Green’s nonprofit foundation has the stated purpose of spreading the gospel of Napoleon Hill. Mr. Green does his job quite well, promoting the works of Hill through the publication of books, and with annual charitable donations that the Hill Foundation makes to the University of Virginia at Wise.

Over the phone, Green continues listing off the names of people who have credited Hill as a great influence on their success. But I interrupt to explain that I’d already read the official 1995 biography of Hill and that I’d love to see the unpublished autobiography that it draws from. Despite the Napoleon Hill Foundation’s loose affiliation with the University of Virginia, I’ve been told by the school that the archive is private. I futilely ask again to see the manuscript.

“There’s nothing in that autobiography that’s not in A Lifetime of Riches,” Green tells me, referring to the official biography first published in 1995. He’s clearly getting agitated with me at this point so I move on and ask for a recommended reading list; something that he can email me when he gives it some thought. I tell Mr. Green I’d like to stay in touch as I become more acquainted with Hill and his writings. I’m informed that this would be just fine.

Green follows through on his promise, even offering to send me a copy of one book. I tell Mr. Green that he doesn’t need to send me a copy, but that I appreciate the offer. I ask yet again, this time over email (journalists sure are persistent jerks), for access to the Napoleon Hill archives. His reply, as I would come to learn, would perfectly capture the business strategy and legacy of Napoleon Hill more than any single book ever could.

Mr. Green wouldn’t permit me access to the archive, but he’d be happy to show me around Napoleon Hill’s hometown of Wise, Virginia for a day. All he’d need from me is a “donation” of $5,000 (£3,962). I didn’t take Mr. Green up on his offer.

Who is Napoleon?

I’ve spent the past two years, off and on, doing my best to research Napoleon Hill’s life without the aid of the private Hill archive that’s so closely guarded from the prying eyes of journalists. And from what I’ve pieced together, Hill was one of the most unlikely motivational writers in history. Even if you ignore the fact that he was a serial swindler.

Hill tried his hand at a number of businesses with varying degrees of legitimacy. He was an executive at a lumber company, he was part owner of a candy company, and he made a go of it as a magazine publisher. But at every turn, there was some kind of shady dealing that would cause his business ventures to crumble. Promoters of Hill claim that it was all a matter of bad luck, and Hill’s naivety. According to his biographers, Michael J. Ritt Jr. and Kirk Landers, Hill’s greatest flaw was that he was too trusting. His business associates would take advantage of him by stealing tremendous amounts of money and later pointing the finger at Hill as the thief.

Modern followers of the Hill myth repeat the tales of his many misfortunes as the work of devious people conspiring against their hero. But when you dig a bit deeper—merely inches below the surface—you start to find that the Napoleon Hill story is far more fiction than fact. There are only so many times that a man can be arrested for the sale of unlicensed stock, altering checks, and outright theft, before you have to question the official history.

The ghost of Hill’s fingerprints can be found on some enormous U.S. industries. Hill paved the way for business and spiritual gurus like Tony Robbins and Deepak Chopra. Donald Green rightly notes that Hill’s writings have had an incredible influence on the leaders of American capitalism. But as we’ll come to learn, this probably isn’t a good thing.

After poring through Napoleon Hill’s life at length, it’s hard for me not to reluctantly empathise on some level with this man who so boldly and earnestly believed in the American Dream. It’s an alluring ideal, however flawed. But ultimately Hill used his ambition and belief in that ideal to build a legacy based largely on lies and deceit.

Napoleon Hill was a deeply troubled soul, suffering bouts of depression and loneliness as he struggled to become a financial success. Constantly on the move, he believed that success came through confidence and visualisation. But behind every upbeat quote and promise of future riches, Hill had a darkness that could not be contained. With every breath he uttered there was a kind of intellectual and spiritual impotence underneath; a cacophony of buzzwords echoing through the skyscrapers of Chicago and the airwaves of Hollywood. And it was his words that would both render him a prophet, and destroy the lives of those closest to him.

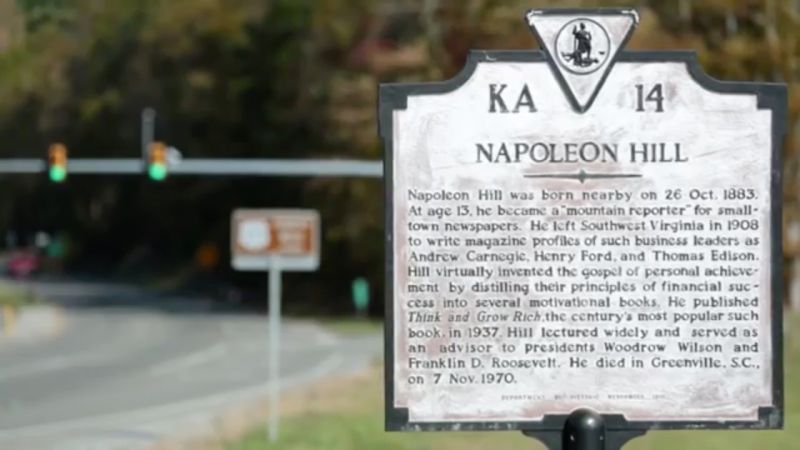

Virginia State Historical Society roadside marker for Napoleon Hill (YouTube)

Oliver Get Your Gun

Oliver Napoleon Hill was born in 1883, the son of James Hill, an unlicensed dentist and occasional moonshiner, and his mother Sara. Napoleon wouldn’t stop using his first name until around 1908, though as a child his family would affectionately call him Nap.

Hill’s early life is described as one of solitude and frustration after his mother died of an illness when he was just nine years old. A year later his father would remarry—a woman named Martha, who by Hill’s account was the one person who kept the mischievous Nap on the straight and narrow. The young Napoleon would regularly get into trouble with a pistol that he’d carry around the backwoods of Virginia at the tender age of twelve. But Martha encouraged Napoleon’s education and especially his writing. She even bought him a typewriter in 1895.

“If you become as good with a typewriter as you are with that gun,” Napoleon later recalled his stepmother saying, “you may become rich and famous and known throughout the world.”

So Napoleon started writing for a small weekly newsletter whose stories were sometimes picked up by small newspapers in Virginia. As his biographers explain:

Napoleon soon became a prolific source of stories. His writing was unpolished, if not crude, but he compensated with unbounded verve and a vivid imagination. Indeed, he later recalled that when news was scarce and there weren’t stories to tell, he simply made them up.

This knack for storytelling, and outright deceit, would come to define the life of Napoleon Hill—a young man who would embrace fakery as he strived to make his way in life through the sale of dreams. It’s perhaps fitting that much later he would be charged under something called the Blue Sky Laws in Chicago. Throughout his life Hill was selling the promise of blue skies for everybody, if only they’d follow his proven model of success. Proven, that is, by anyone but Napoleon Hill.

Officially, Napoleon Hill supporters are probably aware of two or three of his marriages. In fact, he was married at least five times. This would perhaps not be worth mentioning except for the circumstances surrounding his first two marriages—the two that are largely missing from the official stories of Hill.

Hill’s first marriage occurred when he was just 15 and got a girl pregnant. According to the official Hill biography, which is the only known record of this marriage, the young girl’s father angrily demanded that the two be married. But not long after the wedding, “Napoleon’s bride confessed that he had not fathered her child.”

The marriage was annulled, though it’s unclear why this young girl would claim that the 15-year-old Napoleon was the father if this wasn’t the case. But it wouldn’t be the last time that the official record of Hill’s life would erase one of his alleged children.

Not a Cent Was Missing

By the age of seventeen, young Nap had graduated high school and set off for Tazewell, Virginia to attend a business school. Hill then went to work in 1901 for Rufus Ayres—coal magnate, businessman, and the former Attorney General of Virginia.

Ayres was said to be impressed with Hill who, according to the official biography, “compensated for his youth and five-foot six stature by adopting the appearance of a serious young executive; ram-rod-straight posture, impeccable double-breasted suits, immaculately pressed white shirts, conservative bow ties, and white hankerchiefs neatly posed in the breast pocket.”

After working for Ayres for just six months, Hill was promoted to work as a clerk in one of Ayres’ coal mines in Richlands, Virginia. It’s after accepting this position that we start to hear stories in the official history of just how honest and trustworthy Hill was—never taking a penny that he didn’t earn. But they all start to sound like a man loudly proclaiming his ethical fortitude just a little too strongly.

One anecdote includes a bizarre incident in which the cashier of a bank owned by Ayres went on a bender one weekend. In a drunken haze at some nearby hotel the cashier supposedly dropped a gun, which discharged and killed a black bellboy. Hill claims to have heard about the incident and rushed to the scene, interviewing “the only eyewitness.”

Hill goes further to claim that he went to check on the bank at which the cashier worked. The cashier had inexplicably left everything unlocked over the weekend, including the vault. Hill described the scene as one of chaos with, “the money scattered around as if a cyclone had hit.”

Hill wired Ayres to let him know all that had happened, but curiously, despite all the scattered money, there was no evidence that anything had been stolen. At least according to Hill. “He faithfully counted the money, balanced the books, and discovered that not a cent was missing,” according to his biographers.

“I could have appropriated fifteen to twenty thousand dollars or perhaps more without the slightest indication I had taken the money,” Hill allegedly wrote in his unpublished autobiography. But he didn’t take a cent. At least according to him. And his employer, the honorable Rufus Ayres, was so grateful for Hill’s honesty and leadership skills in a time of crisis that he was supposedly promoted to be manager of an Ayres coal mine, with 350 men under his charge.

The 1995 New York Times book review of the Hill biography reads between the lines and goes so far as to say that Hill “covered up” the killing after vouching to the coroner that the death was accidental and paying the expenses for the black bellboy’s burial. “As a reward, his employer made him manager of the mine,” the New York Times explained.

Hill was 19 years old.

Take the Money and Run

The official biography of Napoleon Hill more or less skips over the period covering 1903 until 1908. There’s vague talk of Hill considering law school, writing part time forBob Taylor’s Magazine, and taking a job as sales manager at a lumber yard. But from newspaper and court records of the time, we learn that there’s a good reason that worshippers of Hill might want to breeze past this time of his life. One glaring omission from the official history is Hill’s second marriage and his new daughter.

On June 17, 1903 Napoleon Hill married Edith Whitman at the home of the bride’s father. The Tazewell Republican newspaper reports on this fact the following day, identifying Hill as “Oliver N. Hill, from Big Stone Gap, Va.” As I mentioned earlier, Hill wouldn’t discard the name Oliver until sometime around 1908.

On March 23, 1905 a baby girl was born, Edith Whitman Hill—named after her mother. By September of 1905 Napoleon, Edith and their six-month old daughter moved to Marbury, Alabama and lived there briefly until Hill sent his wife and child back to live with Edith’s father in Tazewell, Virginia. By June of 1907 Napoleon had moved himself to Mobile, Alabama and was getting involved in the lumber business. The Acree-Hill Lumber Company was incorporated in Alabama on June 28, 1907. But Napoleon had plenty of extra-curricular activities.

It turns out that throughout his marriage to Edith, Napoleon was visiting a number of prostitutes in cities throughout the South. Or, as his business associates would call them, “women of ill-fame.”

As one of Napoleon’s former friends would testify about a business trip in 1906:

Soon after we reached Bluefield, [West Virginia] we went to a house of ill-fame, between 8 and 9 o’clock of that night, and Mr. Oliver N. Hill, within a few minutes after arriving there, took one of the girls to a room in the same house, and stayed with her until about 12 o-clock that night. Both of the women who stayed at this house were of easy virtue and Mr. Hill went there for the purpose of having sexual intercourse with these women. He admitted to me that night when were [sic] going to the hotel that he had had sexual intercourse with the girl that he took to the room.

Napoleon and Edith’s 5-year marriage was filled with turmoil and violent outbursts. At one point, Napoleon took their young daughter without telling his wife, leaving the baby with Hill’s mother in Virginia and threatening never to return her. In a letter dated January 24, 1908, Napoleon wrote to his wife saying, “I am leaving the country where you’ll never bother me. You can only communicate with me through my father, and not unless he thinks best.”

By early April of 1908, just three months after writing to his wife, Edith had gotten her baby back and filed for divorce, claiming that Napoleon was “a man of violent and ungovernable temper,” and that he treated both her and their child with “disrespect and cruelty.” This cruelty included periods of violence, when Napoleon would allegedly throw the toddler on the floor and bed and proceed to choke her. The elder Edith also alleged that she was constantly under the threat of violence and that Napoleon had at least once threatened to kill her on a street in broad daylight, claiming he would “blow her brains out.” The testimony given at the divorce proceedings by Napoleon’s former business associates and friends also outlined many incidents of infidelity with prostitutes.

As far as I can tell, Hill never showed up to court to contest the divorce, but that may have been the least of his worries in 1908. Napoleon Hill was arrested in May for altering checks, though he was later acquitted of that charge. The more public fraud was his lumber business, the Acree-Hill Lumber Company. Throughout that year Hill had taken between $10,000 and $20,000 worth of lumber on credit from various suppliers as far away as Georgia, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Indiana. He had been selling off the lumber as quickly as he could in Alabama, accepting only cash, and virtually any amount that he was offered. This, of course, raised plenty of suspicions from the buyers, not to mention the lumber sellers in Alabama who were being undercut at obscenely low prices.

Hill was telling his business partner, J.O. Acree, that he had found new investors in the business, thus the extra mountains of cash that seemed to be pouring in were simply a product of good business connections. But by June, Mr. Acree—who was either an accomplice to Hill’s fraud or realised that something shady was going on—sold his entire stock in the company to Hill.

By the second half of 1908, word quickly spread that Hill was committing fraud, and every businessman in the lumber community was looking for him. In September of 1908 Hill went on the run from his office in Mobile, Alabama.

From the October 17, 1908 issue of the Pensacola Journal:

The whereabouts of O. N. Hill, said to be the president and general manager of the Acree-Hill Lumber Company, is causing considerable anxiety among creditors of the concern in the state and several other lumber section. Hill has not been at his office since September 8.

Nobody could seem to find Hill, and the newspapers and trade journals started calling the hunt for Nap the “Acree-Hill Sensation.” As the November 1, 1908 issue of The Lumberman explained:

Hill left the city almost a month ago, at which time he gave it out to his stenographer that he was going to visit a few mills, and since that time she has not heard from him.

Warrants were issued for Hill’s arrest in Alabama, the US Postal Service was investigating Hill for mail fraud, and I found record of at least one lawsuit filed against Hill in October of 1908 by the Babcock Brothers Lumber Company in Indiana. Bankruptcy proceedings were filed in US district court, though it’s unclear how Hill evaded authorities.

All we know for certain is that by December 1908 Hill had fled to Washington, D.C., ready to reinvent himself with a new name and a new backstory as an automobile expert, educator, and salesman extraordinaire. This is when Oliver N. Hill would start introducing himself by his middle name, Napoleon.

The Fiction of Andrew Carnegie

According to the official legend of Napoleon Hill, 1908 was a pivotal year in the best way possible. Years later, Napoleon would claim that it was in 1908 that he met with Andrew Carnegie in the millionaire’s 64-room mansion in New York. It was there that Carnegie supposedly revealed to Hill the “principles of achievement,” his concept of the “mastermind alliance,” and the ultimate secrets to financial success.

According to Hill, Carnegie would later introduce him to the most powerful businessmen in the country for interviews about what made them so successful. It would be a 20-year mission, Carnegie supposedly explained to Hill. Napoleon wouldn’t receive financial compensation, but would instead simply learn the secrets of business success. Carnegie allegedly introduced Hill to the likes of men like Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Alexander Graham Bell.

In fact, Hill would claim that Carnegie invited him to stay for an entire weekend to learn at the feet of Carnegie and start Napoleon on his journey. But, of course, none of it was true. Between the domestic disputes, divorce, and fraudulent business deals in lumber, Hill spent much of 1908 simply trying to evade the authorities. One of Carnegie’s most respected and thorough biographers has found no record that Hill and Carnegie ever met. The book that was produced from the Carnegie meeting is clearly a product borne solely of Hill’s imagination.

Opening Hill’s book at any random page and reading the drivel passed off as Carnegie’s own words is a fun game. As just one random example from page 97 in my copy:

HILL: Will you tell me, in the simplest words possible, just how one may control this wheel of fortune? I would like a description of this important success factor which the young man or young woman just beginning a business career may understand.

CARNEGIE: First of all, to control the wheel of fortune one must understand, master and apply the 17 principles of achievement. I have already named five of these principles, and I might here suggest that these five, if properly applied, will carry one a long way on the road toward success in any calling.

Imagine for a moment Andrew Carnegie, or any industrialist of the early 20th century talking like that. Seventeen principles of achievement? That’s the kind of strategy rarely found outside organisations that make it their business to sell advice. Carnegie was not known to be in that business, though his distant cousin Dale would certainly get into it with his 1936 book How to Win Friends and Influence People.

Mr. Hill Goes to Washington

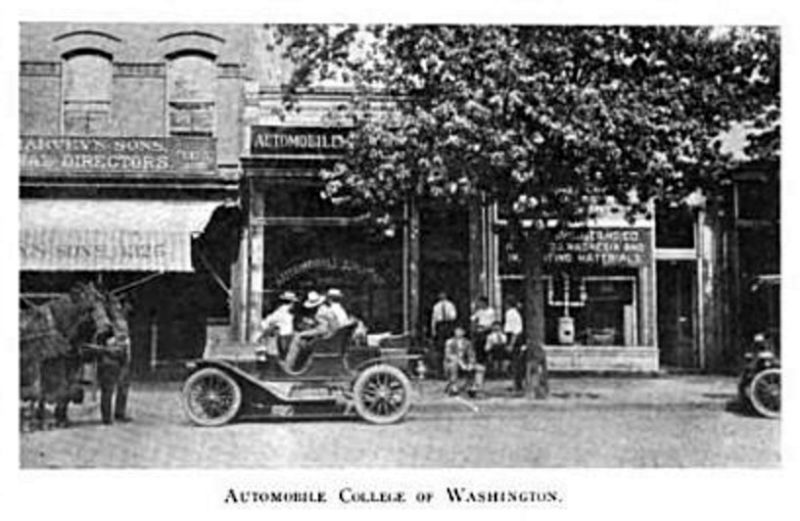

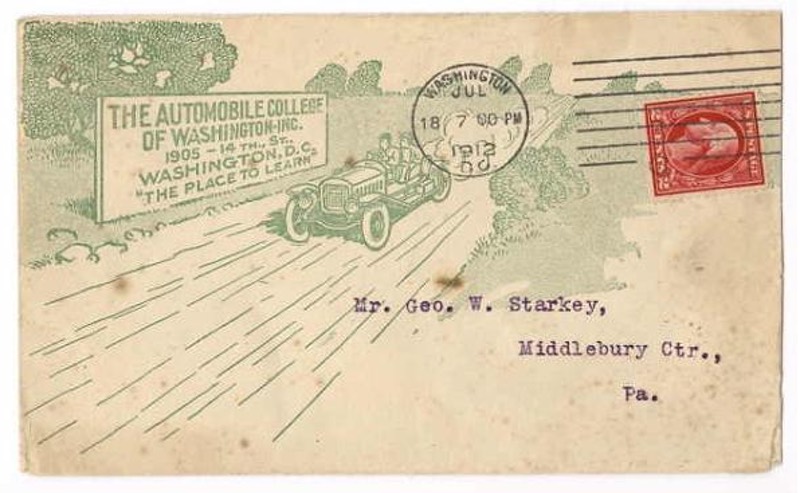

In reality, 1908 was an incredibly tense time for Hill. In December of 1908, he was recently divorced and hiding from a number of people to whom he owed money. That’s when Oliver transforms into Napoleon. Having fled Alabama, it’s in Washington, D.C. that Hill first joins the Automobile Club of Washington and soon after starts the Automobile College of Washington as president in 1909. Hill took out ads in the newspapers surrounding Washington explaining that with just six weeks of training anybody could become an expert in assembling cars in the burgeoning automobile market.

By May of 1909 the newspaper ads promised that Hill would be at the Rammel Hotel in Alexandria, Virginia every Sunday morning interviewing potential recruits for his prestigious college, where graduates would learn how to earn anywhere from $75 to $200 per week. ($200 was roughly the equivalent of $5,000 in today’s dollars.) But at this point you might not be surprised to learn that Hill’s automobile college had an angle that was not so transparent to its “students.”

Photo of the Automobile College of Washington from the August 11, 1909 issue of The Horseless Age magazine (Google Books)

Hill had set up the Automobile College of Washington with himself as president, R.H. Blakesley as vice president, and L.J. Murphy as secretary and treasurer. But much like Hill’s venture into lumber, it wasn’t long before Hill’s partners fled.

From the October 10, 1909 edition of the Washington Post:

Napoleon Hill, president of the Automobile College of Washington, has bought out the other members of that corporation and will manage the school himself. Mr. Hill states that from the present outlook the season of 1910 will far surpass previous ones.

Hill’s “college” was actually a way to get free labor for building cars. “Students” were paying for the pleasure of producing Washington-brand cars for the Carter Motor Corporation in 1910 and 1911. The Carter company had struck a deal with Hill’s “school” and got free labor from “students” who were toiling away constructing vehicles in a Washington warehouse.

It was in D.C. that Hill met Florence Elizabeth Hornor, a high school student, sometime in 1910. She came from a wealthy family in Lumberport, West Virginia and it wasn’t long before the two were married. It was Hill’s third marriage and would produce three children over the coming years.

Curiously, three men of the Automobile College were married all within a week of each other in June of 1910—and none of them told their friends or business associates that they were doing it. It’s unclear why there was such a flurry of semi-secret marriage at the Automobile College during just one week, but it was odd enough that the local newspapers took notice.

As the June 28, 1910 edition of the Washington Herald explains:

When President Hill took his car out of the college garage Thursday morning the motor students who helped him lay in a stock of gasoline and strap on an extra tire hadn’t the slightest idea that he was harboring matrimonial intentions.

He drove the car around to the home of Miss Horner, who graduated from Central High School last Wednesday and is a niece of former Gov. Atkinson, of West Virginia. Ten minutes later the machine was whirring along the level highway that leads to Marlboro.

The ceremony was performed there quietly, and that same evening the car stole back to Washington, carrying Mr. and Mrs. Hill. They will be at home to their friends at the Earlington apartments, Mount Pleasant, in about a week.

Hill and Miss Horner met three months ago while the pretty high school girl was still working for her diploma in the class rooms at Central.

But something was amiss. While Hill was honeymooning, his various business partners and suppliers were jumping ship. A notice in the July 16, 1910 Washington Heraldannounces that one of Hill’s partners, Ernest M. Hunt had dissolved their business partnership in the Mount Vernon Inn. The July 19, 1910 Washington Post announced that another partner on a different venture, Clarence J. Warnick, was alleging that Hill had stolen a car (a crime for which Hill was arrested) and wanted the National Automobile College to be put into receivership.

A year after their marriage, Napoleon and Florence would have their first child James, named after Napoleon’s father.

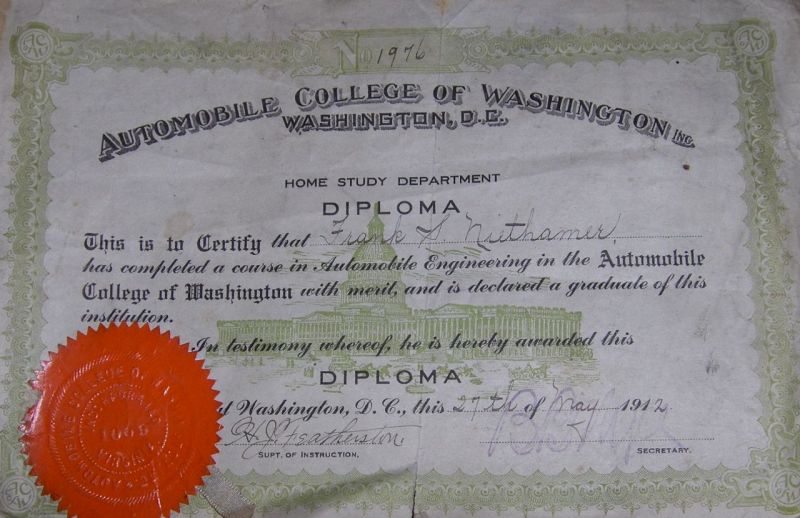

Diploma from the Automobile College of Washington dated May 27, 1912

After the Carter Car company had to declare bankruptcy in early 1912 (presumably because the people building its cars had no idea what they were doing, and former “students” who couldn’t find work were alleging fraud) Hill was not deterred. He continued the “college,” pivoting his means of bringing in revenue. His college would no longer put an emphasis on teaching students to build cars. Instead, he’d teach people how to sell them.

Hill wasn’t the only one running schemes around the newfangled automobile in the early 1910s. But he was certainly the most “daring and enterprising, and therefore the most interesting” as the magazine Motor World described it.

In an article titled “Pointing the Easy Route to Getrichquickland,” the April 11, 1912 issue of Motor World laid out all the ways in which Hill’s college was actually a scam. The article describes the college’s slick marketing materials and devious “questionnaires” that were primarily designed to see how much money the prospective student had.

Among the very first of the college’s amazing propositions offered is “our automobile agency plan.” A conspicuous page in the catalog is devoted to the setting forth of the “plan,” and is headed, “Our course prepares you to earn $4,800 a year, or more.” Briefly, the “plan” is that “all those who become students of this college will be made sales agents for the Washington Cars, shown in this catalog, the price of which is $2,250 for either model, fully equipped. We will allow our students a commission of $400 on each car they sell.

The literature goes on to say that “students” can earn $3 per head for everyone they sign up for this scheme and buys a car. Sound familiar? Multi-level marketing companies use similar tactics. And as a matter of sheer coincidence, I’m sure, in 2014 the Napoleon Hill Foundation gave the “Napoleon Hill Award” to one of the most notorious multi-level marketing companies in the United States, Organo Gold.

Promotional material for the Automobile College of Washington sent to prospective “students” in 1912

On November 11, 1912 Napoleon and Florence had another baby boy, naming him Napoleon Blair Hill. The baby was born deaf and without ears but despite his handicap, the elder Napoleon was determined to see his son succeed. Even if this meant denying him the ability to communicate like other children born without the ability to hear.

As Hill’s official biography recounts:

In the years to come, despite intense fighting with both family and schoolteachers, Napoleon would never allow the boy to learn sign language. He was determined to singlehandedly teach his deaf son to speak—and even to hear.

Despite borrowing heavily from the bank, and getting $4,000 from his new wife’s family to invest in the Automobile College, it folded in 1912. The Hill family moved to Lumberport to be with Florence’s family, and Napoleon took a job with the Lumberport Gas Company. He quickly grew restless and for whatever reason decided that he’d find his fortune in Chicago.

This decision, as Hill’s biographers explain, would establish a pattern for his marriage, “and ultimately Hill’s family life was the price he would pay for wanting to make his own way in the world, and do it on his own terms.”

“False Charges” Abound

In Chicago his wife’s family helped him get a job at the LaSalle Extension University by way of a letter of recommendation from a family friend who happened to be a judge. Not long after, Hill got stationery printed up with the letterhead: “Napoleon Hill, Attorney at Law, 2715 Michigan Avenue, Chicago.”

Aside from the fact that Hill never went to law school, Hill’s own admiring biographers concede that this was an “exaggerated claim” and that “there is no record of his having actually performed legal services for anyone.”

It’s unclear why Hill left LaSalle in less than a year but by 1915 Hill went into business with three partners, buying a franchise of the Martha Washington Candy Company. They renamed their business the Betsy Ross Candy Shop, with Hill as president. Curiously, one of his partners, Ernest M. Hunt, is a man whom Hill knew from a previous partnership in the Mount Vernon Inn back in West Virginia. It’s unclear what their angle on that business was. But whatever their former relationship, the candy company partners quickly pushed Hill out for some unknown transgression.

“To gently urge me toward the ‘grand exit,’ they had me arrested on a false charge and offered to settle out of court if I would turn over my interest in the company,” Hill would write later. It’s unclear what the false charge was exactly. Hill filed suit against his former partners, and claimed to have won a victory in some Chicago court five years later. This, of course, could not be confirmed outside of Hill’s own writings.

Following his brief dabbling in the candy business, Hill clearly believed that the way to riches was in establishing schools. In September of 1915 he started the George Washington Institute, residing in Chicago but incorporated in Delaware. “Where he got the capital for his venture is a mystery,” his official biographers note, but it likely came from yet another loan by his wife’s wealthy family.

Hill’s unaccredited school in Chicago was set up to teach the “principles of success” and self-confidence. Perhaps too much self-confidence, as Hill urged his students to write numerous letters to newspapers in support of Napoleon Hill’s “race for a seat in the United States Congress.” Later, some would claim that Hill privately aspired to nothing less than the presidency of the United States.

Some students of the George Washington Institute would accuse Hill’s unaccredited school of fraud, and it too had a very short life. According to his biographers, Hill returned the favor of one student’s criticism by alerting the FBI of the German-American kid’s “suspicious activities.” The student was supposedly arrested for the duration of World War I.

Hilariously, Hill shows up in Chicago newspapers in February of 1917 claiming that he’s going to sue the Illinois Central railroad because the lighting in their passenger cars was harming his eyesight. “I have been using the I. C. trains less than two months, yet I have been compelled to use glasses for the first time in my life,” Hill told the Chicago Daily Tribune. “It is my intention to begin suit against the company.” I haven’t found evidence that Hill ever did bring a suit. But even in the increasingly litigious culture of the early 21st century, a lawsuit about poor lighting on public transit would probably be considered frivolous. It seems Hill was trying to make a buck literally any way he could.

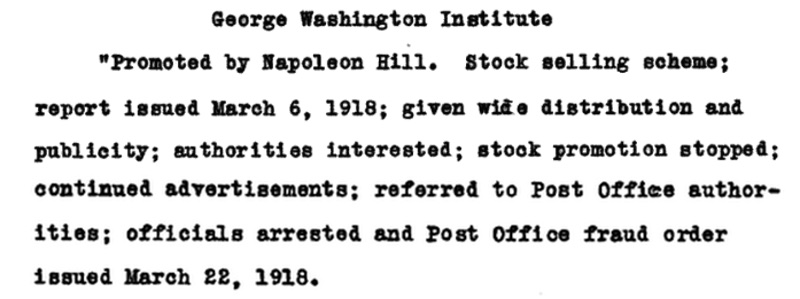

By March of 1918 Hill’s George Washington Institute was starting to draw negative attention from government regulators as a “stock selling scheme,” as the Better Business Bureau put it. As the magazine Postage explained, “While it appeared on the face of the operation that he sought students for the educational course he offered, there was evidence that his chief object was to sell stock in the enterprise.”

Excerpt from the Better Business Bureaus Annual explaining that Napoleon Hill’s George Washington Institute had been shut down, published in 1919

Hill had established the school with a capital valuation of $100,000, divided into 10,000 shares. He gave himself 51 percent of the stock and was selling shares to his students at $10 per share. The only problem was that Hill’s $100,000 valuation was complete junk.

As the assistant Attorney General of Illinois, Raymond Pruitt, told the Chicago Daily Tribune, “Investigation reveals that the physical properties and other assets of the institute appear insufficient to warrant the $100,000 capitalization placed upon it.” With just a few dozen desks, a mimeograph and printing supplies the school would be “liberally appraised at $1,200.”

By early June of 1918 warrants were issued for Hill’s arrest. He was charged with violating the Illinois Blue Sky Law. It didn’t help Hill’s case that he had set up the an official-sounding dummy corporation called the First National Trust Association and was mailing students offers to lend the money for their tuition at the George Washington Institute, “to be repaid in installments, at 5 per cent interest.” The name First National Trust Association sure sounded official. But it was just Hill, ostensibly offering student loans (at 5 percent interest, of course) to pay himself.

When the warrants were issued on June 4th, Hill promised to turn himself in. But Hill wouldn’t emerge until four days later, posting $2,000 bond. The July 1918 issue ofModern Methods magazine still had an article by Napoleon Hill titled “How to Sell Your Services” listing Hill as the Dean of the George Washington Institute. Hill claimed that he was simply a “forceful writer” and that his business was in no way illegal. It’s unclear whether he had to pay back any money to students of the George Washington Institute, but based on how quickly he shows up in newspapers with another scheme the follow year, he clearly emerged relatively unscathed.

All that said, by summer of 1918, Hill’s wife Florence and her family had had enough. Napoleon was occasionally visiting his family in West Virginia during the lead up to his arrest (enough to get Florence pregnant with their third child David, born on October 26, 1918) but he spent most of his time during this period in Chicago, New York, and allegedly back to Washington D.C.

Nap Serves His Country

Instead of reporting the facts surrounding his administration of a fraudulent college, the official story of Napoleon Hill tells a different tale about his time from 1917-18 on the tale end of World War I. Many years later Hill would claim that he was approached by President Woodrow Wilson for help with the war effort. Apparently Wilson was willing to pay handsomely for Hill’s services, but Napoleon, a true patriot, wouldn’t take any money. Curiously, Wilson didn’t even have an idea for what Hill might do to help fight the war. He just wanted him involved.

“President Wilson wanted to place me on the government payroll at a rather attractive salary, but for once in my life, I had the privilege of vetoing the president of the United States,” Hill would later write, according to his biographers. “Thus, I assigned myself a job which made it essential that I go the extra mile, with no thought of what I might receive for my services.”

That’s right. Nearly broke, Hill turned down a salary from the President of the United States in order to serve his country for free. That job? Producing propaganda materials for US businesses to encourage Americans who were toiling away making the machines of war.

But the story gets even better. Hill even claimed that he was sitting in the White House with Wilson in 1918 during the negotiations over Germany’s surrender.

“I was sitting in President Wilson’s office as he read the decoded message from them,” Hill claimed. “His face turned white as snow. When he finished reading he handed the documents to me and left the room. He was gone for about fifteen minutes. When he returned, he handed me a couple of sheets of paper on which he had written his reply to the Germans, which ended with three questions related to the terms of the armistice.”

Yep, patriotic Napoleon Hill was about to be asked by the President of the United States for his advice on the terms ending World War I.

“After I read his reply, he asked if I had any suggestions to add to it. I said, ‘Yes, Mr. President, I would suggest a fourth question. I would ask whether the request for an armistice has been made on behalf of the German people or the German war lords.’ ‘Of course,’ exclaimed the President, ‘for that will put them on notice to get rid of their Kaiser before they can get an armistice.’ And it did just that.”

I’ve found no evidence that Napoleon Hill ever met Woodrow Wilson, let alone was in the White House during the negotiations of the armistice. In fact, Hill’s own published writings of the time don’t mention this event at all.

It’s incredibly difficult to find original copies of his magazines, presumably because its circulation was relatively small, but thankfully the Napoleon Hill Foundation has made a business of publishing and republishing his earlier works. In Napoleon Hill’s First Editions we get a glimpse of many excerpts from his work in the late 1910s and early 20s. The volume even includes entire articles. From there we learn the truth—or at least a version of the truth that didn’t yet include exaggeration and lies about his ties to powerful politicians.

The September 1921 issue of Napoleon Hill’s Magazine describes precisely what he was doing on November 11, 1918:

That was armistice day, as everyone knows. Like most other people, I became as drunk with enthusiasm and joy that day as any man ever did on wine. I was practically penniless, but I was happy to know that the slaughter was over and reason about about to spread its beneficent wings over the earth once more.

He goes on to explain that he sat down at his typewriter and was inspired to start Hill’s Golden Rule magazine. But Hill, the consummate self-promoter—a man whose entire career would later hinge on his supposed associations with the most powerful men in the world—doesn’t mention his critical participation in this historic event at all.

Instead, it’s pretty clear what Hill was doing after the George Washington Institute was closed in Chicago in the summer of 1918. He indeed started Hill’s Golden Rulemagazine, but its primary purpose seemed to be less about inspiring businessmen and more about helping companies swindle investors. Hill got mixed up with a man named S.E.J. Cox and his wife N.E. Cox from Houston. The Cox couple owned the General Oil Company and were looking for investors. Even if they had to lie to get them.

Hill helped the Cox couple spread news about just how well their company was doing. The Federal Trade Commission charged Hill on October 1919 with using his magazine for fraudulent advertising. Hill wrote an article in the April 1919 issue of Hill’s Golden Rule magazine titled “An Interesting Man and His Wife Who Have Made $1,000,000 for Other People.” Sounds like classic clickbait if you ask me.

The FTC charges spelled out how the piece had “numerous false and misleading statements, known by the respondents to be false and misleading, and published by them for the purpose of furthering their plans and purposes.”

But it wasn’t just Hill’s Golden Rule, which was a magazine that had a relatively small circulation. Hill started numerous magazines and tabloids over the years, with nearly every article exclusively written by Hill under very pseudonyms. In Houston, Hill helped the Cox couple start a magazine ironically called Truth.

Aside from “greatly exaggerating fortunes to be made out of oil stocks,” this Truthmagazine also touted the benevolence of the Cox family in running an enormous charity for the young men returning from the ravages of World War I. The FTC charged Cox with lying when he said that “he was holding in trust checks amounting to more than $1,025,000 to be used for the payment of scholarships for worthy and needy boys and returned soldiers.” Apparently Cox, through Hill’s magazines, was claiming that by buying stock in his oil company not only were you making a great personal investment, but you were contributing to a great charity at the same time.

Aside from publishing schemes and bogus colleges, dubious “charities” would become another hallmark of Napoleon Hill’s repertoire.

The Perversion of Hill’s Golden Rule

Throughout his career, Napoleon Hill preached the gospel of the Golden Rule. But it’s perhaps not the same Golden Rule that you’re thinking of. Hill would give lip service to some kind of karmic ideal that by helping others, you’d find goodness deliver back to you at some point. But at other times he showed his cards a bit more.

In the February 1920 issue of Hill’s Golden Rule magazine:

It seems ridiculous to refer to the Golden Rule as a “weapon,” but that is just what it is—a weapon that no resistance on earth can withstand!

The Golden Rule is a powerful weapon in business, because there is so little competition in its application.

When we look at the way that Hill lived his life, Hill’s understanding of the Golden Rule meant that people would become indebted to you for providing something to them. It was a weapon. Rather than “do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” he believed that by providing something to someone or simply showing them kindness, they owed you something in return.

Hill learned early on that an easy and cost-effective way to get your name in the press was to present people with awards for their demonstration of the Golden Rule. In May of 1922 he awarded a chiropractor by the name of Dr. B.J. Palmer Hill’s “Golden Medal.” Hill claimed that the award was based on 150,000 votes cast by subscribers of his magazine, among them from places as far away as Japan, Italy, Australia, and England. Who came in second? Woodrow Wilson.

The idea of it all was absurd on its face. But it gained Hill national coverage in newspapers and magazines around the country. It’s doubtful 150 people cast votes in Hill’s little magazine poll, much less 150,000. But his award-giving tactic would later let him gain access to some of the famous people he so dearly wanted to meet. Hill pops up in the newspapers of the early 1920s, proudly handing out the Napoleon Hill Golden Rule Medal to little known people for their “service to humanity.”

It was under the banner of “the Golden Rule” that Hill partnered with Chaplain T. O. Teed to start the Intra-Wall Correspondence School in 1922. The charity would provide educational materials for prisoners in Ohio so that they could lead productive lives once they left prison. Unsurprisingly, the charity’s main focus was the sale of subscriptions for Hill’s magazine and newly developed prison correspondence courses.

Hill petitioned for the release of Butler R. Storke, an inmate who was serving two years for check forging—a similar crime for which Hill himself had been arrested and acquitted in 1908. Storke was on conditional release and would head the “charity” because, by some accounts, it was his idea to begin with.

“What we are trying to do is to meet mentally these men who are shut off from the outside world,” Hill would tell one Ohio newspaper in September of 1923. “We’re going to prove to them that they have something to look forward to, then put in their hands the tools with which they can carve out their future.”

One of the most scandalous newspaper articles on Hill comes from late 1923. In it, the author lays out all the people trying to track him down for one reason or another—most often for unpaid debts. And most ethically damning, the article exposed his wholesale pocketing of money that was supposed to go to “charity.”

Hill was traveling from city to city in the early 1920s on his mission to collect donations for his Intra-Wall Correspondence School. His constant movement around the country was not necessarily out of wanderlust, of course, but rather to stay one step ahead of the law. Hill left New York in August of 1923 bound for Atlanta only to jump back up to Ohio.

The December 21, 1923 edition of the Mansfield News in Ohio illuminated Napoleon’s misdeeds. The Mansfield News told of one church in Shelby, Ohio where Napoleon made his pleas for charity the previous August:

Hill made such an impression upon his hearers that more than $1,000 was collected by him through various sources—even the school children contributing to the fund—and the money was to be devoted to giving men inside the prison a chance.

Adjusted for inflation, $1,000 is about $14,000 in today’s currency. Other newspaper accounts claimed it was $800. But whatever the exact number, it was a lot of money. Hill’s schemes of the early 1920s were as brazen as they were despicable. He’d hop from town to town (often targeting churches), promising that every penny he collected was going to help men in prison start a new life. But every penny was making its way to Hill and his associates’ pockets by one way or another.

By December 31, 1923 the Mansfield News ran an update on Hill’s schemes, under the headline “Money collected by Hill in Shelby never received says prison warden and chaplain.” The prison warden for the Ohio penitentiary where Hill was supposed to be sending this money, P.E. Thomas, told the local newspaper that they never saw a dime. And neither had the prison chaplain who helped Hill start the Intra-Wall Correspondence school in the first place.

“I am reliably informed by Chaplain T.O. Reed, who is connected with such school that none of this money was ever received by said school,” Thomas told the Mansfield News.

Amazingly, it was Hill who claimed that the chaplain and his associates were the ones who corrupted the Intra-Wall Institute’s humanitarian mission. Hill blamed the lost cash on men of God, and much more shrewdly on the man who he’d helped bail out of prison. Storke, the check forger released to help start the school was sent back to prison. Storke changed his name on various occasions throughout the 1920s, and would spend the next two decades in and out of prison for embezzlement and other sordid business deals.

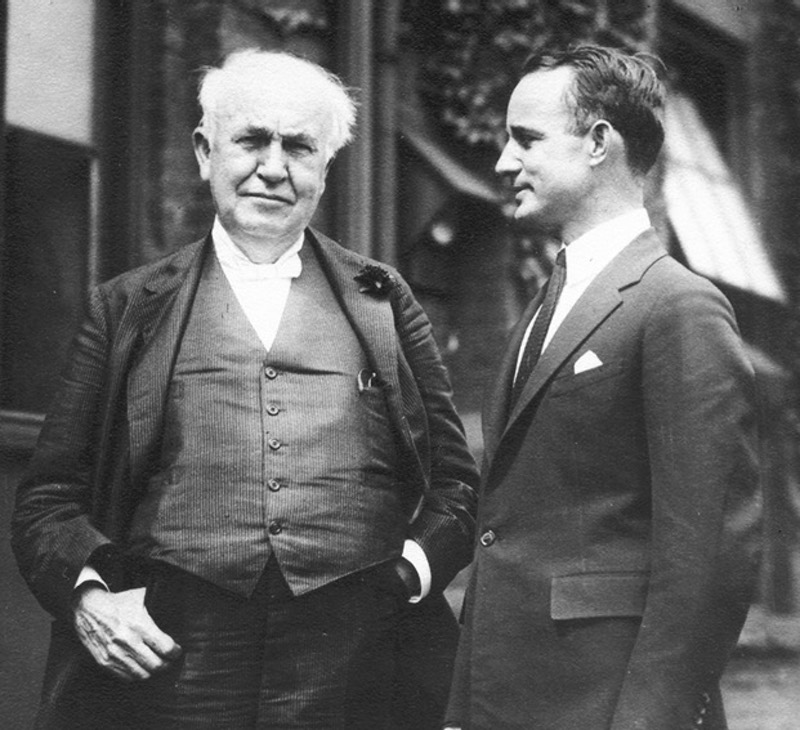

Napoleon Hill and Thomas Edison

Napoleon Hill claimed to have learned the secrets of success through interviews with hundreds of incredible celebrities and businessmen. But outside of Hill’s own writings there’s virtually no evidence that he met with these people. What we do have, however, is this picture:

Photo of Thomas Edison with Napoleon Hill after Hill presented Edison with an award that Edison returned (1923)

This photo of Napoleon Hill standing awkwardly with Thomas Edison is the only photo of Hill with any of the famous businessmen (let alone Presidents) he claimed to have interviewed over the course of his decades-long career in studying the secrets of success. But the real story behind the photo is told in the December 1923 issue ofSpecialty Salesman Magazine, in an article called “Destroyers of Confidence.”

The article explains Hill’s “audacious stunt”:

Hill figured on how he could have a picture made with Thomas A. Edison, so he could give him a medal. He sent a press agent over to announce that “Mr. Hill, one of the leading magazine writers, wished to attend the Edison Convention of Dealers.” Of course, he was welcome. He asked Mr. Edison to pose with him, a request he could hardly refuse.

Hill circulated the photo far and wide with the caption:

Two of America’s famous men—Thomas A. Edison (left) and Napoleon Hill. Mr. Edison is the inventor of the talking machine, the electric light, the moving picture and scores of other things that serve mankind. Mr. Hill is the editor of Napoleon Hill’s magazine and The New Philistine Magazine and believes in making the Golden Rule the rule of all human conduct. Edison was born of poor parents and began his career as a news butcher on a train. Hill began as a laborer in the coal mines. Both have risen to fame through their own efforts.

During that brief meeting Hill gave Edison his medal. But by one account, “Mr. Edison returned the medal without comment.”

A Convenient Fire

One of the most intriguing questions surrounding Hill’s claims about meetings with famous people in the first three decades of the 20th century is why they never show up outside of Hill’s own writings. Well, there’s a convenient explanation for all that.

According to the official biography of Hill, he returns to Chicago at some point in the mid-1920s to find that the items he had in storage were in a building that had burned to the ground.

Gone were dozens of letters and notes from Woodrow Wilson, including his approval of a Hill proposal that the president used to sell war bonds. Gone were the autographed pictures of Wilson, [Alexander Graham] Bell, and others. Gone was President Taft’s letter endorsing Hill for employment. Gone was the series of letters from Manuel L. Quezon, who corresponded with Hill prior to becoming president of the Philippine Commonwealth.

Well, there you have it. What ever happened to Hill’s early correspondence and photos of famous men? They all burned up in a fire.

Murder in the Midwest

In the mid-1920s Hill bounces around Ohio and Indiana, ready to start anew yet again. But the Midwest of the 1920s was a dark and seedy place for a number of reasons. Today, we romanticise the gangster era of Chicago in the 1920s and 30s. It’s remembered in the early 21st century as a cartoonish landscape of anti-hero mobsters—James Cagney types—taking on the coppers with tommy guns and cigars firmly planted in their mouths. But as in Chicago, the big cities and small towns of Ohio and Indiana could be dangerous places in the 1920s.

Unlike the movies, very real blood was being spilled over political power struggles, illegal booze, and virulent racism. And Napoleon Hill would get caught up in the middle of it all as he toured Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana, making friends and enemies with journalists, politicians, and the Ku Klux Klan.

The rise of the Klan in the 1920s is remembered (if it’s recalled at all by Americans today) as an exclusively Southern problem. But the Klan had a surprisingly strong presence in northern states as well, like Oregon, Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana. In fact, many of Indiana’s politicians and police officials of the 1920s were card-carrying Klansmen. So it’s no surprise that Napoleon Hill’s ventures in the Midwest during the mid-1920s would see him get mixed up with all kinds of seedy figures. But oddly enough, it’s Hill’s supposed association with an upstanding newspaperman in Ohio that would land him in the most trouble.

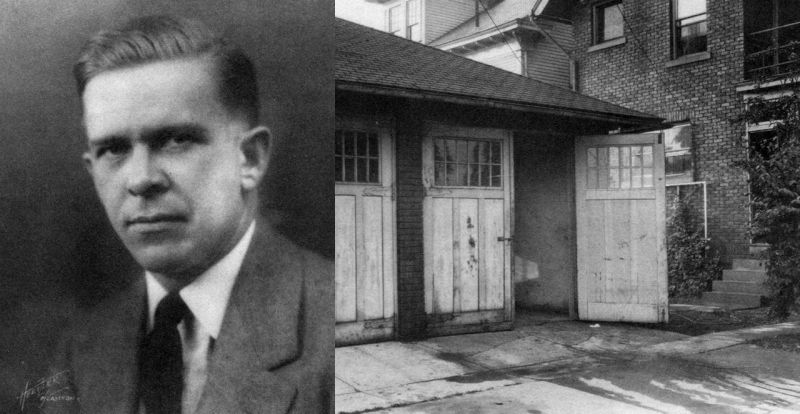

Donald Mellett in 1925 (Stark County Historical Society/Murder of a Journalist) and the garage where he was murdered (Cleveland Public Library/Murder of a Journalist)

Donald Mellett was a respected newspaper publisher in Canton, Ohio in 1925. He reported on both mob and police corruption in the Canton Daily News and courted controversy through his muckraking. Mellett came from a family of journalists and struggled for years at tiny newspapers in his home state of Indiana and then Ohio. When he was brought on as editor of the Canton Daily News, the paper initially gained readers through an emphasis on subscription sales over street sales—a long-term, unconventional model for the newspaper industry at the time. But the conservative pro-Prohibition, anti-vice Mellett soon began losing advertisers as he exposed Canton’s expansive underworld of prostitution, drug smuggling, and payoffs to police.

Not a huge city by any means, Canton was simply one of many cities across the US that was experiencing an explosion in organised crime. Canton’s red light district was known as the Jungle, according to Thomas Crowl’s 2009 book Murder of a Journalist, home to over a hundred brothels by 1925. And it counted amongst its ranks plenty of police officers who were being paid to look the other way—whether it was booze, sex, or sometimes murder. Mellett’s campaign against it all would be his undoing.

Mellett had been editor of the Canton Daily News merely a year before he was murdered. He was gunned down outside his own garage on July 16, 1926—assassinated by either underworld figures, corrupt police, or most likely a conspiracy involving a mixture of the two. There was immediate outrage in the journalism community. One of their own had been assassinated, making it a national story for months.

Napoleon Hill later claimed Mellett was a friend, and Mellett was supposedly impressed by Hill’s lectures and teachings on the science of success. Hill later claimed that Mellett also wanted to help Hill publish an eight-volume book on the subject of success and how to achieve it. According to Hill’s biographers, Mellett had assembled the $50,000 needed to publish Hill’s multi-volume tome of success right before tragedy struck.

As Hill’s biographers tell it, Napoleon was nearly assassinated as well. “Hill escaped a similar fate only because car trouble had delayed his return to Canton until the next morning.” The very next day Hill supposedly received an anonymous phone call threatening his life and “left immediately, not even pausing to pack.” He fled to West Virginia, according to his official biographers, living out the next year in hiding from both Ohio police and mobsters. But that story contradicts itself even in his own biography, because by all accounts he spent the next few months trying to get a lecture tour started in the Midwest. And even though Mellett got plenty of threatening phone calls in the lead up to his assassination, there’s no reason to believe that Hill would be a target. Also, as the editor of a struggling newspaper (second in a town of two newspapers), even if Mellett showed interest in Hill’s writings, it’s unlikely that Mellett had assembled $50,000 for the publication of some grand work by Hill. Mellett was far too busy antagonising the local police and booze-runners to go fundraising to get Hill’s books published.

In the August 27, 1926 issue of the Courier-Crescent in Orrville, Ohio (just 25 miles outside Canton) Hill is noted as giving public lectures and touting his association with the slain newspaperman. Even people who disagreed with Mellett on any number of issues (including perhaps most fervently his advocacy of alcohol prohibition), saw his murder as a direct assault on the First Amendment. Mellett was a martyr, and whatever Hill’s actual associations with Mellett, Nap was ready to capitalize on it. In the months after Mellett’s murder, Hill was still in Ohio. Hill charged that the assassination was carried out by organised crime leaders “under the protection of city police” in Canton.

“Mellet was one of the most courageous men I ever knew,” Hill said during an August 26th lecture in Orrville. “He was absolutely fearless. To get at the source of the criminal operations and the inefficiency in the police department, he found that the civil service commission must be removed. Immediately a conspiracy against Mellett was organised in the police department, which derives its authority from the civil service commission.”

Hill was flatly saying that the police were as much responsible for Mellett’s assassination as any organised crime syndicate. And he was probably right. That’s what other newspapers were charging as well. Mellett’s editorials in 1925 and ‘26 called for the firing of police officers by name. He even had the Canton Police Chief, S.A. Lengel, ousted by the Democratic mayor before the Republican-controlled city council reinstated him.

By October of 1926 Hill was still roaming around Ohio and Indiana. He appears in court in Indianapolis testifying about political corruption in Indiana, but it had nothing to do with Mellett. As the Associated Press reported on October 21, 1926, Hill was a witness for the prosecution, giving grand jury testimony about the Ku Klux Klan’s involvement (and potential murder conspiracies) with politicians.

From the AP:

Efforts were made also to find Harvey Bedford and George Elliott, both of whom formerly were active in the Klan here. Napoleon Hill, a lecturer who was said to have a contract with Bedford and Elliott was in the grand jury room during the afternoon.

It’s unclear from the research I’ve done so far what kind of contract Bedford and Elliott, or the Klan in general, may have had with Hill. But even Hill’s biographers note that his lecture tour of Indianapolis included a talk delivered to a meeting of the Ku Klux Klan.

By October 26, 1926—Hill’s forty-third birthday and less than a week after his testimony in front of a grand jury implicating the KKK in unnamed misdeeds—his biographers claim that Hill finally went into hiding for real. He’d stay in the backwoods of West Virginia, broke and alone, throughout 1927. Judging from the newspaper records of the time, this appears to be true. But who he was hiding from is still unclear. Had he pissed off the Klan? Mobsters of Ohio who were bootlegging and allegedly selling drugs to children? Was it the police or politicians after him? All of this is still a mystery as far as I can tell.

Posing For Pelton

Sometime in late 1927 or early 1928, Hill emerged from hiding, ready to embark on yet another publishing venture. Hill moved to Philadelphia and his alleged plans with Mellett would not go to waste. Hill would see his eight-volume work, now titled Law of Success, published one way or another. He’d burned plenty of bridges through his schemes over the years, so he had few people to turn to for money. Hill eventually approached a man he didn’t know personally, a publisher in Connecticut named Andrew Pelton, to get his ambitious, rambling work into the hands of Americans.

Pelton was a true believer in the prosperity self-help movement. One of Pelton’s first publishing successes was the 1919 book Power of Will by Frank Channing Haddock, a substantial figure in the New Thought movement who likely had an impact on Hill’s later work. Nearly all of Napoleon Hill’s ideas were borne of the New Thought movement of the late 19th century and early 20th. Proponents of the philosophy included Mary Baker Eddy, who would go on to start the Church of Christian Science. As with any religion or religious philosophy, there are plenty of disagreements about what the proper way to practice might be, but the fundamental idea running through all of New Thought is that ideas and thoughts have very direct and material actions upon the world. Hill’s contributions to the New Thought movement simply added that as long as you could influence the world using only your mind, why not get filthy stinking rich in the process?

Hill was completely broke in Philadelphia and had to appear to his potential publisher as a man of success and grace. So he borrowed money from his brother-in-law, rented an enormous suite in a swanky Philadelphia hotel, and played the role of the successful businessman for Pelton. Hill’s biographers tell of Nap flashing a large wad of money around the hotel lobby, lavishly tipping every bellboy and clerk he saw in anticipation of Pelton’s arrival. And it seemed to work, despite the fact that Law of Success was mangled garbage as far as any literary merits were concerned. Pelton agreed to publish the book anyway and by mid-1928 the royalties begin to come in, however small.

Hill’s biographers even concede that the first volume of Law of Success wasn’t a very good book, but that the people who believed in him allowed the book to eventually find an audience and helped it sell briskly. Napoleon would bank on his supposed association with powerful men time and again.

“Law of Success might well have been discarded as the ravings of a lunatic but for the fact that much of Hill’s most improbable conjecture was spun from the musings of men like Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell,” Hill’s biographers wrote. “Thus anchored in respectability, these passages stimulated readers to wonder, to ponder life on a grander scale more than any self-help book ever has, before or since.”

If it hasn’t become clear already, Napoleon had more or less abandoned his wife Florence and their three sons by the late 1920s. They were all living with Florence’s mother, only seeing Napoleon when he’d peek his head in for short bursts, usually to get money. In letters he wrote to his wife he promised that once the big money from Law of Success started pouring in he’d “buy a country home for you out of the first accumulation, and then we will begin to store a goodly sum of the remainder in the bank so I will never again be in the position of having to accept ‘alms’ as I did last year. I am cured of that forever.”

By early 1929 the money indeed started to flow. According to his biographers, he was averaging about $2,500 per month (roughly $35,000 adjusted for inflation) from royalties. Always having to previously pretend that he was wealthy, Hill had his first legitimate success that allowed him to flaunt his money. He quickly bought a Rolls-Royce (two Rolls-Royces by his own account in a book years later), and an enormous house in the Catskill Mountains of New York sitting on six-hundred acres. But whatever his true royalties fromLaw of Success were, they weren’t really enough to cover his decadent lifestyle. Hill bought his gigantic estate, named Shagbark, with a number of investors. He told them that he was going to turn the property into the “world’s first University-sized Success School.”

“Eventually, they intended to also build and sell vacation homes on the grounds for successful people who wanted to mix traditional vacation pleasures with the opportunity to brush up on the principles that would enhance their continued success,” his biographers would later write.

Local newspapers were excited about the prospect of a “Success Colony” being opened in their neck of the woods. “Mr. Hill will build two additional lakes on the place, remodel the clubhouse, and generally beautify the place,” the Catskill Mountain Star gushed in June of 1929.

By July, Florence and their three boys had moved into the luxurious estate and Napoleon was hard at work getting his elite utopian community off the ground. It was the first time that all five members of the Hill family were living under the same roof. But it wouldn’t last for very long. Napoleon, always the man on the run, was bored with their idyllic home in the middle of nowhere. He longed for the excitement of the city and quickly set out on “speaking tours,” as his biographers described it.

By autumn of 1929 Hill had set up an office in New York City, an inauspicious time for the American economy at large. The stock market dipped and dove wildly throughout September and October of 1929, culminating in the great Wall Street Crash of October 24, 1929. By the following week, the stock market had been decimated. It was the unofficial start of the 1930s and the decade-long Great Depression.

At first Napoleon seemed unaffected by the crippling downturn in the economy. Or so he claimed. But by mid-1930 their opulent home was foreclosed on and Florence and their children were back in Lumberport, West Virginia, living with Florence’s family. Napoleon, hard at work on his next book from his office in New York, wrote lovingly to Florence, assuring her that everything would be okay once his next book hit the shelves. But his latest work, The Magic Ladder to Success, was “stillborn” as his biographers put it. Napoleon and his family were once again broke, and Florence kept their kids fed and clothed through the continued generosity of her family.

Curiously, during this period of turmoil Hill’s biographers quote a letter from Napoleon to Florence about his idea to offer scholarships to high school students who submit the best idea for how to turn Law of Success into a movie.

“We plan to organise a sales force and take the contest to all the high schools all over the country,” Hill wrote. “If I get it over it will make me rich in a year. If I do not I might go to jail . . . . The idea is that every contestant would need the Law of Success textbooks in order to get ideas from them for the contest.”

The ellipses in that quote are that of the biographers. It’s unclear what Napoleon is writing about when he explains that he “might go to jail.” But frankly, it could be referring to any number of things—past, present or future. If Hill is referring to the idea of starting a contest only as a ruse for selling his book as a textbook, then yes, that would probably have been illegal in some way or another. Hill was always dancing the thin line that separated brilliant marketing technique and outright fraud, often escaping the law because Hill would claim it was always the former and never the latter.

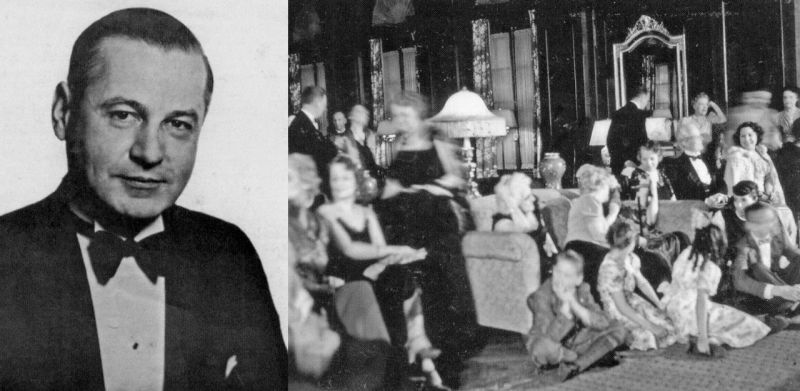

Excerpt about the halting of sales of Napoleon Hill stock in the May 17, 1930 Brooklyn Daily Eagle in New York

Law of Success would never be made into a motion picture, but Hill was very interested in the movie business by 1930. In fact, he helped produce the first Mormon feature film ever. The production was not without its hiccups, however, as the state of New York had to step in and halt the financing scheme dreamed up by Napoleon. Hill and his Mormon protege, Lester Park, were selling unlicensed stock under a company they’d set up called the Corianton Corporation. It seems Park and his relatives’ interest in the film were sincere, but per usual, Hill’s tactics to acquire financing were skirting the law. The production of the film was delayed many times and by August of 1931 investors or “stockholders” asked that the company be put into receivership. Flora B. Horne, an investor and Mormon historian in Salt Lake City helped bring the suit, asking for $5 million in damages. But the film, Corianton: A Story of Unholy Love, an epic tale from the Book of Mormon, was ultimately produced, despite being a box office flop outside of Utah. Today it’s nearly impossible to find the film, though Brigham Young University has a 16mm print—one of the only copies known to exist.

It’s unclear how much money Napoleon Hill extracted from the corporation before the film’s very limited release.

Nothing to Fear

Hill spent the early part of the 1930s devising different magazines and constantly seeking investors. In New York he started Inspiration Magazine under a new company he called the International Success Society. It lasted two issues before he moved to Washington, D.C. and started the International Publishing Corporation of America, a company set up to yet again sell unlicensed stock. All the while Hill was jumping from city to city—Philadelphia, Baltimore, among others—to seek investors in all kinds of dummy corporations and stock-selling schemes. Once he made Washington his home base he turned the International Success Society into the International Success University, a correspondence course that yet again was little more than a way to extract gobs of money from people around the country.

But it was in 1933 that Hill would supposedly have yet another brush with political power. Years later, he would claim that he was approached by the Roosevelt administration to help instill confidence in the American economy. As Hill’s biographers note, his “personal record of his relationship with Franklin Delano Roosevelt and FDR’s administration was surprisingly scant,” and their political views were polar opposites, with Hill being an “arch-conservative.” But somehow they made it work, and Hill’s ideas were injected into FDR’s New Deal program, supposedly imploring labor unions to be more cooperative with management at various companies. Again, this was all according to Napoleon Hill, an anti-union arch-conservative who claimed to have written some of FDR’s speeches and even to coin the phrase “we have nothing to fear but fear itself.”

Much like his alleged work for the Wilson administration in 1918, Hill supposedly demanded that he not be paid for his contributions to his country. All he wanted was a dollar per year. Which is again quite curious, given the fact that Hill was broke, living off the largesse of his wife’s family. His refusal of a decent salary supposedly earned him the nickname “Nap the Sap,” from Roosevelt’s press secretary. Though if anyone ever called Napoleon that it most certainly wasn’t anyone from FDR’s administration.

Needless to say, I’ve found no evidence outside of Hill’s own writings that he ever met President Roosevelt, wrote any of his speeches, nor acted as a trusted advisor to him.

By 1935 Florence filed for divorce from Napoleon. Divorce was illegal in West Virginia at the time, so she flew to Florida and spent a week there, where she won an uncontested divorce. Napoleon had abandoned his family from practically day one, enjoying only brief visits where he was known by his sons as much for his temper as for anything else. And Florence was through with tolerating, let alone financing from a great distance, his schemes and unfulfilled promises to both his “investors” and his family.

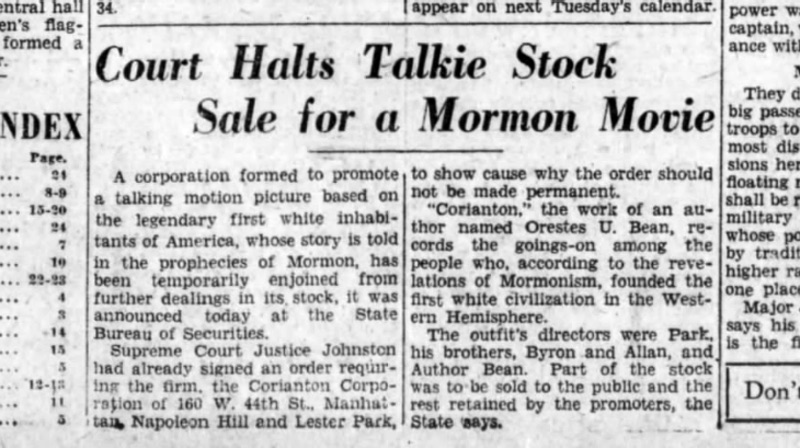

Napoleon Hill reading his own book, Think and Grow Rich, in 1937 (Library of Congress)

Think and Grow Rich

After his divorce, Hill found himself yet again penniless and lonely. He could no longer count on money from Florence’s family to keep him afloat, and he so desperately wanted a companion. One imagines that outside of his visits to “women of ill-fame” he struggled to connect with members of the opposite sex. During one lecture in Knoxville, Tennessee sometime in 1936 he rather frankly and publicly stated that he was in search of his “dream girl.” A woman in the audience, Rosa Lee Beeland, jumped at the chance to talk with Hill personally after the lecture. They set up a time to talk at length the following day.

“When I arrived he met me at the elevator, escorted me to his study, and without inviting me to be seated, started immediately to tell me his story,” Beeland would write later. “We talked for more than five hours. We compared notes and spoke very plainly and frankly.”

Where his “study” was exactly and what precisely they were comparing notes about is unclear, but as Beeland would write, “Before I left we were engaged. Then we were married.” After less than 48 hours, the 53-year-old Napoleon and the 29-year old Rosa Lee had plans to marry.

Almost immediately Hill and Beeland (now Mrs. Hill) would begin work on his most famous book, Think and Grow Rich. Without any money, the newlyweds moved in with one of Napoleon’s sons Blair and his wife Vera in their small Hell’s Kitchen apartment. Blair was the only one of Hill’s sons that would still talk to him. But it made for a very stressful living arrangement, to say the least. Vera was the primary victim of the ill-tempered Napoleon in their cramped quarters.

“[Vera] bore the full brunt of Napoleon’s ability to unashamedly heckle and hound people he didn’t like,” Hill’s biographers explain. After a few months of verbal abuse from her father-in-law, Vera moved back to West Virginia and Blair followed. Before leaving for West Virginia, Blair gave Napoleon and Rosa Lee a $300 loan so that they continue their work on Hill’s latest book, now alone together in Blair’s New York apartment. Despite following his wife to West Virginia Blair and Vera would eventually divorce.