Source: Doing business in -35°F degrees | Greg Sarber | Energy Moving Forward | BP Moving Forward

Doing business in -35°F degrees

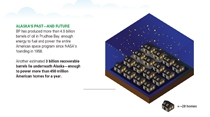

As a BP operations superintendent in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, Greg Sarber knows a thing or two about living in a place that looks and feels not-of-this-Earth. When just walking outside requires special clothing, equipment and a seemingly endless list of safety protocols, it’s easy to see how Sarber would come to compare working in Prudhoe Bay to being on another world. Prudhoe Bay is an environment of extremes. Located 250 miles north of the Arctic Circle on Alaska’s North Slope, Prudhoe Bay experiences winter temperatures that dip below -50°F, massive blizzards accompanied by 40 mph winds, and months of perpetual darkness – or sunlight – depending on the season. Despite these obstacles, BP has spent the last three decades helping to develop Prudhoe Bay into the largest oilfield in North America. The field has produced over 15 billion barrels of oil since it began production in the late 1970s. And the past and future success of this vital field depends on a strict adherence to an effective and comprehensive safety system.

Reading the weather

Every day begins with a daily safety meeting to brief workers on current weather conditions. Severe weather periods are broken down into three safety phases, which reflect varying levels of danger. Even Phase I weather, the mildest of conditions, can be exacerbated by near total darkness; from the middle of November until late January, the sun never rises. Under a Phase II front, which includes heavy snow drifts and sheet ice, workers are required to travel in convoys of two or more vehicles and remain in constant radio communication. According to Sarber, the BP team experiences Phase II events “all the time.” In Phase III conditions, only critical or emergency travel is permitted. To understand the severity of a Phase III weather system, which occurs periodically throughout the winter, Sarber suggests thinking of a hurricane of snow, with winds reaching 70 mph. It’s no surprise that heavy-duty gear is required to live and work in such conditions.

Suiting up

Beyond the wind and snow, cold, brittle air can make hypothermia, frostbite and dehydration real dangers, even in the spring. “It can be a beautiful spring day in Prudhoe Bay and it’s 11 below outside”, Sarber says. “And if it’s 20 or 30 below, the cold is hard to describe. It’s almost painful.” As a result, all workers must carry their winter gear, even when traveling to and from the airport -- especially since the weather can change rapidly. When outside, “normal work wear” for Sarber includes insulated boots and gloves, long underwear, and a hard hat with an insulated liner that wraps around his face. For all workers that go out on location, their outer-layer must be fire-retardant.

Keeping things running

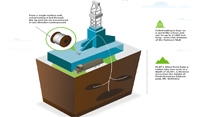

The environment is a challenge to not only personal safety, but to the safe operation of tools and machines. The rumble of car engines is a near constant fixture of life on the North Slope; vehicles are sometimes left running 24/7 so the engines won’t freeze. But even idling a pickup’s engine won’t stop its tires from developing flat bottoms. The extreme cold compresses the air in auto tires; leave a car or truck motionless for long enough, and the tires will go “square.” “It’s a concept that people in the Lower 48 can’t relate to, but it’s what we deal with every day on the slope”, Sarber noted. As transportation is essential, Prudhoe Bay’s gravel road system undergoes regular maintenance due to the heavy truck traffic. And the fight against corrosion is constant. Every year, BP conducts more than 100,000 pipeline inspections on the North Slope, using techniques such as ultrasonic and radiographic imaging. In 2008, BP commissioned a $500 million refurbishment project that included a new 16-mile oil transit line system, the renovation of the main Prudhoe Bay oil delivery system and the installation of cutting-edge leak detection. BP is also deploying wireless corrosion sensors to detect unexpected changes in the wall thickness of pipes. Maintenance accounts for more than $100 million in costs every year.

Building in 50-below

Heated buildings sit on stilts to prevent melting the frozen soil underneath (referred to as the permafrost) and subsequently sinking. The 800-mile-long Trans Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), which BP helped build, sits on stilts for the same reason and is raised even higher in some areas to allow caribou herds to pass underneath. But in a surprising twist, the winter months are some of the Bay’s most active because it’s only during the winter that the tundra is hard enough for major construction and the use of heavy equipment. The frigid temperatures also allow “ice roads” to be created so workers can access some of the hardest-to-reach drill sites. By spring, the top layer of tundra – above the permafrost – becomes too soft for construction.

Returning to the tundra

Despite the harsh conditions and the challenges they present, people like Greg Sarber, who has spent over a decade working in upper Alaska, continue to return. Sarber insists that the procedural regimens that define daily life on the slope are a perfect fit for him and his co-workers. “We’re all kind of ‘Type A’ people. If a problem is identified, we can solve the problem”, he says. Sarber is also driven by a deep commitment to U.S. energy security. “It’s great to be able to produce oil in America for Americans. It’s a vital thing and it’s a great sense of accomplishment to help do it.”

Despite the harsh conditions and the challenges they present, people like Greg Sarber, who has spent over a decade working in upper Alaska, continue to return. Sarber insists that the procedural regimens that define daily life on the slope are a perfect fit for him and his co-workers. “We’re all kind of ‘Type A’ people. If a problem is identified, we can solve the problem”, he says. Sarber is also driven by a deep commitment to U.S. energy security. “It’s great to be able to produce oil in America for Americans. It’s a vital thing and it’s a great sense of accomplishment to help do it.”

The future of Prudhoe Bay

Life on the North Slope

A path paved in snow

Alaska’s high-tech tundra

Alaska and BP